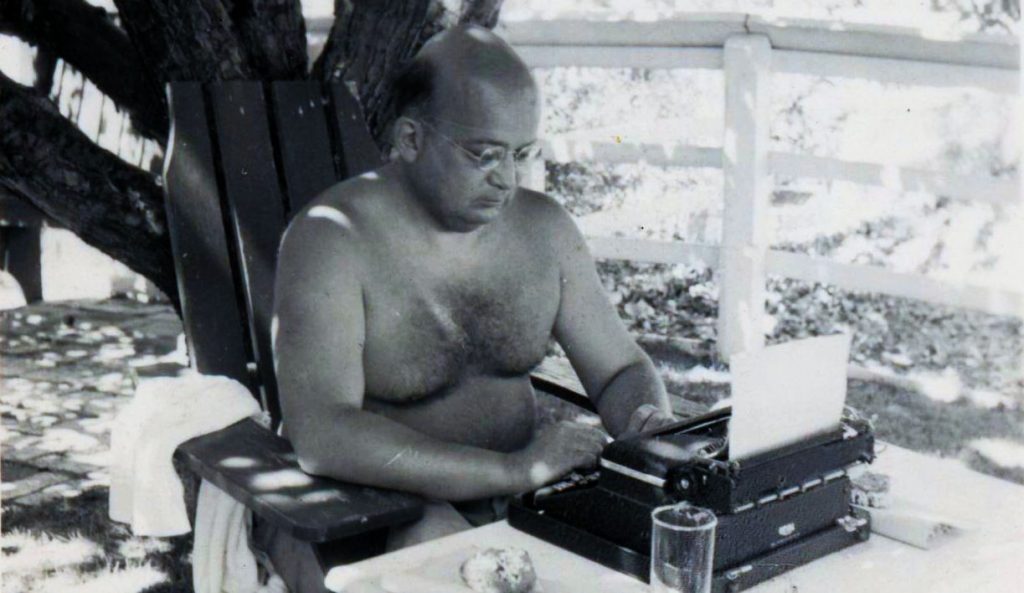

“I used to be shy about ordering a steak after I had eaten a steak sandwich,” he once said, “but I got used to it.”

A.J. Liebling, a critic of the daily press, a chronicler of the prize ring, an epicure and a biographer of such diverse personages as the late Gov. Earl Long of Louisiana and Col. John R. Stingo died yesterday at Mount Sinai Hospital.

Mr. Liebling, who was 59 years old, entered the hospital on Dec 19, suffering from bronchial pneumonia.

In 1935, after about a decade of intermittent employment as a newspaperman. Mr. Liebling went to work for The New Yorker. Since then he had written hundreds of articles for the magazine, many of which later appeared in book form.

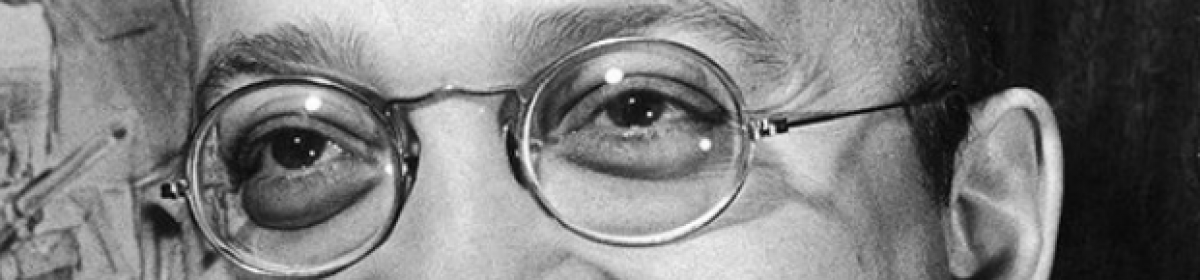

He first came to prominence as The New Yorker’s Paris correspondent on the eve of World War II. Later he followed the First Infantry Division across North Africa and into northern France. Despite chronic gout, a degree of plumpness and extreme nearsightedness, he regularly accompanied combat patrols.

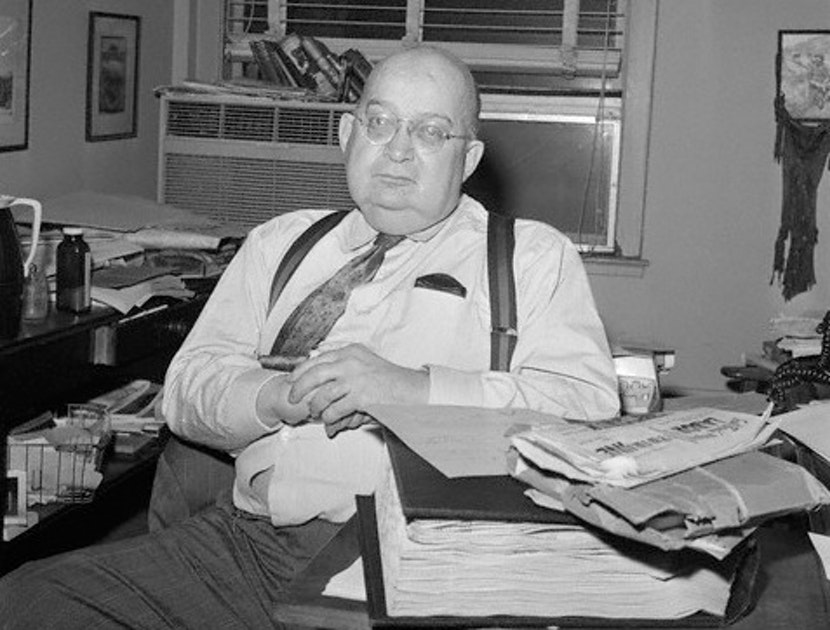

In 1946, he took over the magazine’s “Wayward Press” department, first conducted by Robert Benchley. His perceptive, sardonic articles on such subjects as editorial campaigns for the end of meat price controls, news treatment of the Alger Hiss trial, and, more recently, the newspaper strike here, were widely read.

He resided in Chicago for a while in the late 1940’s, and the resulting dissection, published in 1952 as “Chicago: The Second City,” still possesses the power of creating instant rage there.

He considered Carl Sandburg’s poetic evocation of a brawling, enterprising city outmoded. Mr. Liebling said its cry had changed from “Let me at him!” to “Hold him offa me,” and suggested that the appearance of the city indicated it has been “plopped down by the lakeside like a piece of waterlogged fruit.”

In an extended New Yorker profile that appeared in book form in 1953 as “The Honest Rainmaker,’ he told of Hames A. Macdonald, a man of many occupations who was at the time a racing columnist for The New York Enquirer und the pen name of Col. John R. Stingo. The colonel, now deep in his 80’s, is still a familiar figure in midtown cafes.

Perhaps Mr. Liebling’s most widely read book was “The Earl of Louisiana,” which appeared in 1961, and was based, as usual, on a series of New Yorker pieces. Mr. Liebling took the rather unorthodox view that Governor Long, better known for his eccentricities, was the South’s most effective liberal in recent years.

He had been an amateur boxer in his youth, although, as he observed, he was not in the Ernest Hemingway class for size, skill or literary attainment, This interest was reflected in accounts of major prizefights and sketches of ring personalities that appeared from time to time in the magazine.

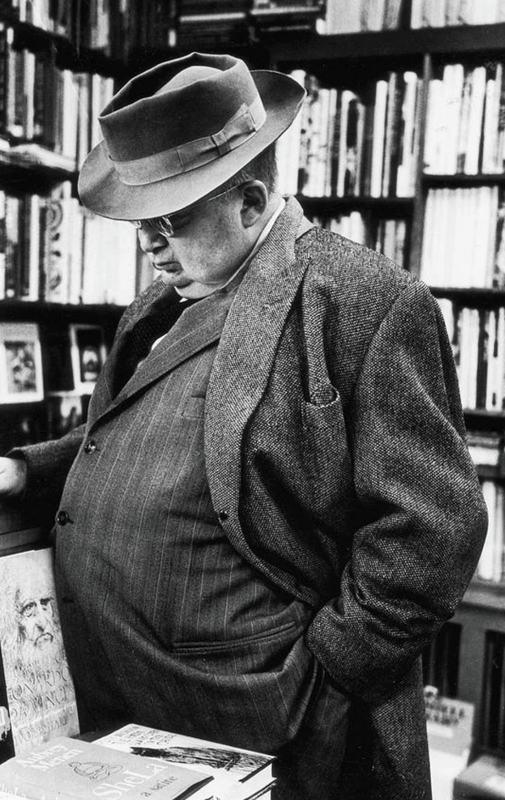

He studied ancient history at the Sorbonne, without much dedication, and became a scholar of the bistros and cafes.

A collection of his articles on boxing, titled “The Sweet Science,” was published in 1956

In the middle fifties he revisited the old battlegrounds of the First Division, reacquainting himself with the delights of Calvados and Norman delicacies he described in loving detail in “Normandy Revisited,” which appeared in 1958.

In “Between Meals,” published last year, Mr. Liebling cast an unaccustomedly tender eye on his growing up in Manhattan, trips to Europe with his parents as a child and his own student days in Paris in the early twenties.

In October of this year, “The most of A.J. Liebling,” a selection from a dozen of his earlier collections, was published.

Mr. Liebling never lost the reporter’s skill of recording facts accurately, but as his style matured it became convoluted, subtle and abounding in unlikely allusions. An account of a Sugar Ray Robinson fight, for example, might be a delicate embroidery on a theme suggested by a medieval Arabian historian to whom he was partial.

Mr. Liebling bore the marks of the gourmet: an extended waistline and rosy cheeks. “I used to be shy about ordering a steak after I had eaten a steak sandwich,” he once said, “but I got used to it.”

Abbott Joseph Liebling was born in New York on Oct. 18, 1904. His father, Joseph Liebling, was a furrier. The son later described him as embodying the Horatio Alger legend in reverse, making his money early and dying broke.

The Son, who was generally known as Joe, was expelled from Dartmouth College for refusing to attend chapel. He enrolled at the School of Journalism at Columbia University, which he later said, had “all the intellectual status of a training school for the future employees of the A. & P.”

Last May, though, on the school’s 50th anniversary, he was one of 81 persons honored as distinguished alumni.

His first job after graduation was in the sports department of The New York Times. One of his jobs was to compile basketball box scores, right down to the name of the referee. One night Mr. Liebling failed to get the official’s name from a high school correspondent and gave it as “Ignoto,” which is Italian for “unknown.”

Deciding he was on to a good thing, Mr. Liebling stopped asking for the referee’s name. In the weeks that followed, Ignoto appeared at games all over the East Coast, sometimes several in a night. The sports editor made inquiries. He didn’t see the joke, and eight months after being hired, Mr. Liebling was dismissed.

He went next to The Providence (R.I.) Journal and Evening Bulletin, where as a reporter and feature writer, he later said, “I oozed prose over every aspect of Rhode Island life.”

In all he spent four and a half years there, interrupted by a year in Paris. He arranged to have his father finance the trip by telling him that he was thinking of marrying a cotton broker’s mistress. There he studied ancient history at the Sorbonne, without much dedication, and became a scholar of the bistros and cafes.

He returned to New York in 1930. Not immediately finding employment, he hired a man to picket the entrance of The World, carrying a sign that read, “Hire Joe Liebling.” The city editor always used the back door, and it was not until the paper had gone out of business that Mr. Liebling caught on with the World-Telegram.

Mr. Liebling wrote hundreds of feature stories during the next five years and gained the familiarity with off-beat New York that he continued to The New Yorker.

He remained active until he entered the hospital a week ago, working on a study of the reaction of the southern press to the assassination of President Kennedy.

Despite the considerable breadth of his published works, it is likely that Mr. Liebling most enjoyed his role as a press gadfly. His favorite themes were the diminishing competition and consequent loss of enterprise caused by merger and sales.

In 1948, when the fist collection of “Wayward Press” articles was published, Mr. Liebling dedicated it “To the foundation of a School for Publishers, Failing Which No School of Journalism Can Have Meaning.”

Mr. Liebling was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honor by the French Government for his work as a writer on French subjects and as a war correspondent. He was the translator and editor of “The Voices of Silence,” a compilation of writings be members of the Resistance during World War II.

He lived at 45 West 10th and had a summer home at Easthampton, L.I.

He is survived by his widow, Jean Stafford, the novelist, whom he married in 1959, and a sister, Mrs. Harold Stonehill. Two previous marriages, to Ann Beatrice McGinn in 1934 and to Lucille Hille Spectorsky in 1949, ended in divorce.

Funeral services will be held at the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Church, Madison Avenue and 81st Street, at 1 P.M. tomorrow.