Library of interest for Downs

From The Guardian

Did the American TV producer David Milch read Pete Dexter’s Deadwood before creating the 2004 HBO drama of the same name? Milch claims he didn’t, but readers of Dexter’s 1986 novel might find that hard to believe. Both Deadwoods begin in the frontier town of the same name, in the Dakota Territory’s Black Hills, in 1876, with the shooting of the Wild West gunfighter Wild Bill Hicock, and choose to find the bulk of their narrative in the aftershocks that vibrate through the town after his murder. Most of their principal characters – Sheriff Seth Bullock and his friend Solomon Star, Calamity Jane, saloon owner Al Swearengen – were real-life historical figures, and Dexter and Milch portray them very differently, but Dexter sees some of Milch’s more left-field ideas – chiefly that of turning Hicock’s historically insignificant friend Charley Utter into a major character – as a little too similar to his own. He has also criticised the TV Deadwood – a show that once featured 63 “F” words in one episode – for its unrealistic overuse of swearing.

This must all be very frustrating for Dexter, who remains terribly underrated novelist. For lovers of historically-themed entertainment, however, it’s a win-win situation. The best way to see the relationship between Dexter’s Deadwood and HBO’s Deadwood is by way of comparison to the relationship between a raw, 1930s blues song and a giant, addictive 70s rock anthem deriving from it: one probably wouldn’t have existed without the other, but they’re both great in entirely different ways.

That said, if you’ve only witnessed the Deadwood of Ian McShane and Timothy Olyphant, Dexter’s stripped down version might take a little getting used to – just as a collection of Robert Johnson songs might, if the only blues music you’d ever heard was The Rolling Stones’s Exile On Main Street. Unlike Milch, Dexter is not so interested in the intricate big-picture politics of a rapidly growing Gold Rush town. His storytelling is on a smaller scale, exploring the small foibles of masculine temper and sexuality, and getting inside the character of Utter: a flawed but well-meaning frontiersman he seems to find more interesting than Hicock. There’s warmth in his characters, but it’s not the same kind you find in their TV equivalents, which is a hyper-real warmth that perhaps has no place in a novel, especially set in a cruel, lawless place where a winter will “take the life out of your face”.

What Dexter and the TV Deadwood do have in common is a mordant, masculine wit, and a flair for casual violence. “He was carrying a leather bag, and smelled like everything he’d touched or eaten in two months,” he writes of a bounty hunter. Hicock’s killer, Jack McCall, is “a weak-looking Irishman with no butt end and a face like a rodent.” When McCall commits his infamous deed, there’s something unexcitable about the scene: it’s no Gunfight at the OK Corral but, perhaps more crucially, you feel like you can smell the spilt liquor, dirty waistcoats and wood shavings.

Of any modern novelist, perhaps only Cormac McCarthy writes more like a man whose spiritual home is the old West. By about page 50, you forgive Dexter for writing “would of” instead of “would have” because by then you’re convinced he was actually there while all this stuff was happening: a wry, taciturn presence in the corner, who stayed out of things, mostly, but could throw a doughty punch or two when necessary.

Yet oddly, this remains Dexter’s only Western novel. His other books have restlessly roamed from the newspaper business (The Paperboy) to a malevolent, bigoted small town (Paris Trout) to the life of a proto-Tiger Woods in noirish 1950s Los Angeles (Train). What links all these novels is a raw, phlegmatic view of the world and a hard-boiled voice that tells you more than any voice in actual hard-boiled fiction probably ever could.

Before Dexter embarked on a career as a novelist, in the early 80s, he was nearly killed in a bar-room brawl, and this perhaps enables him to relate so well to unadorned characters such as Utter, who’ve clearly had the crud kicked out of them a few times, and whose humour “grows an edge” when they drink. Despite what Dexter does to disguise it by putting it in a macho, life or death setting, there’s a beautifully angled, humble comic tone in lines such as (about Sheriff Bullock) “his hat went on his head as carefully as you’d set dynamite” or (about a prostitute reluctant to give a frontiersman a more tender kind of love) “If Lurline needed to cradle something, she would of borrowed Pink Buford’s bulldog” that makes it no surprise that Dexter’s favourite novel of the last 25 years is Richard Russo’s Straight Man or that his latest novel, Spooner, is the kind of epic romp John Irving might have written if he was a fan of boxing instead of wrestling. In the end, it’s perhaps that tone that Milch can thank him most for: something that – maybe accidentally, maybe intentionally – carried over into the TV Deadwood and made for a new, more mischievous and human kind of old West storytelling.

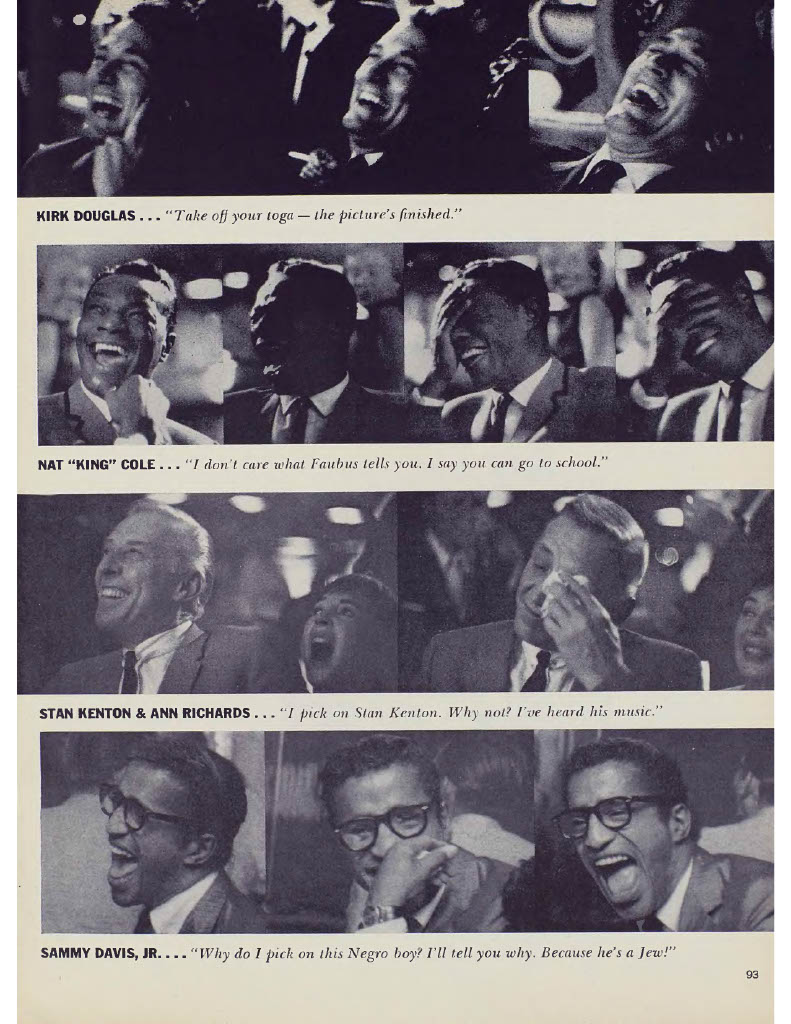

In the midst of a phantasmagoria of worn-out mangled faces, scarred cheeks and necks, twisted, pocked, crushed and bloated noses, missing teeth, brown snags, empty gums, stubble beards, pitcher lips, floppy ears, scores, scabs, dribbled tobacco juice, stooped shoulders, split brows, weary, desperate, stupefied eyes, under the lights of Center Street, Tully saw a familiar young man with a broken nose.

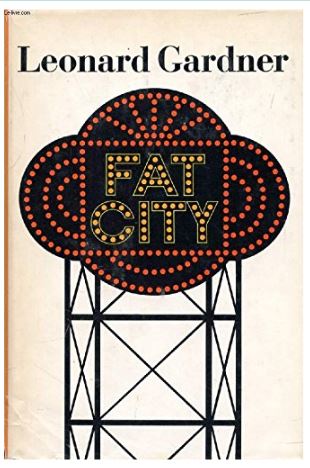

Leonard Gardner

From: The Paris Review

Fifty years ago, in 1969, a boxing novel unlike any other that has seen the light of day, before or since, was published. Fat City, by Leonard Gardner, upends the triumphalist clichés of boxing stories, in which a palooka from nowhere overcomes all obstacles through fierce dedication and hard work and wins the title.

To say that Fat City is about boxing would be like saying that In Search of Lost Time is about parties in Paris or Moby-Dick is about whaling. Boxing is the setting, and it’s one that Gardner knows firsthand. But the novel is about hope, illusion, and love, and the corruption and self-deception that destroy those things. It’s a lean and sinewy novel, without a single surplus sentence. Considered a masterpiece—by Joan Didion, Denis Johnson, and Raymond Carver, among others—the book is still in print at New York Review Books.

Fat City follows two would-be boxers—one, eighteen-year-old Ernie Munger, is on his way up, while the other, twenty-nine-year-old Billy Tully, is in a downward slide. No matter how hard they train, no matter how much they believe in themselves, no matter who they have in their corners, neither will ever get anywhere near a championship belt.

The book is set in the city of Stockton, in California’s Central Valley, where Gardner grew up. Stockton is noted for its high crime rate and its low literacy level. It is the second-largest U.S. city to have ever filed for bankruptcy. Ernie and Billy frequent greasy, fleabag hotels; sweaty gymnasiums with flooded, blocked drains; blistering fields where boxers earn a day’s pay picking onions or tomatoes; and violent skid row bars where patrons nurse their cut-rate shots and beers. In 1972, Gardner wrote the screenplay to adapt Fat City into one of the saddest movies ever filmed, directed by John Huston.

Gardner lives in Marin County, California, about a hundred miles from Stockton. He is now eighty-five, tall, lanky, and cordial, with a full head of hair more brown than gray. He is under contract for a second novel. I caught up with him in Berkeley to talk about the book, its film adaptation, and his life as a writer.

INTERVIEWER

Fat City exposes a reality about the lives of most boxers. I wonder whether you had that in mind when you wrote the book—knowing that you had a truth to tell that was unlike anything that had been published before.

GARDNER

I got into amateur boxing as a teenager in Stockton, and had some amateur bouts, but I never boxed professionally. Still, I felt like I had a story. The opening of the book is based on experience. There was a boxer, he’s dead now, his name was Johnny Miller and he was a ten-round main-event fighter. I’d seen him fight in Stockton, then he just went a little overboard and became kind of a drunk and had to drop out of boxing for a while. One day, I was in a gym punching on a bag—I had a bag in my garage, and I learned how to punch that bag like a wizard. He came in there and asked me whether I would spar with him. And I felt, Jesus, I’ve been acting like I’m a boxer, but I had been boxing only with kids in the backyard. I’d seen him box, but I couldn’t say, No, you’re a professional. He was in really bad shape, but I was still spooked. I was thinking this guy will kill me.

I had dreamed about being a boxer. Out in the garage I punched about ten rounds on the bag every day. You use your imagination and you’re like, I’m knocking the shit out of Sugar Ray Robinson! So I felt, This guy is calling my bluff and I have to box with him. Maybe he had a horrible hangover or something—I don’t know. I was a tall, long-legged kid, and I had footwork. I ran rings around this guy, popping in little jabs. I actually did a good job of surviving. I could pop him with my jab and he’d swing and he’d miss and I’d be out of the way. And so naturally he had to save some self-esteem by thinking, I’ve discovered a great talent here! He said, “You gotta box, kid.”

INTERVIEWER

Books and movies about boxing tend to be about contenders or champion fighters. Even the seedier stories are sort of glamorized. But Fat City is about people who will never in their wildest dreams be contenders.

GARDNER

When I was a kid, Stockton had a population of eighty thousand. It was a hot boxing town, and we never turned out a champion. There was nobody remotely like a champion.

INTERVIEWER

In the book, in the climactic fight, Billy is punched so hard in the ring that he literally sees the world divided into a zigzag. I read somewhere that this was based on your own experience?

GARDNER

I wasn’t trying to be a professional boxer anymore, but I had a friend in Santa Barbara who lived near my ex-wife. A real tough guy, an ex-marine. He asked me to spar with him. And I thought, Well, I don’t have to demean myself. I just assumed we were friends. I’m a little guy compared to him. He has shoulders like this and a little waist. He would run fifteen miles just for the hell of it. He had a heavy bag hanging from the tree and he worked on that every day. He wasn’t actively boxing anymore, but he was one hell of an athlete. So we sparred and I can’t remember whether I went one round or two before he hit me with this shot. I’ve never had a reaction quite like that to a punch. And I told him, “I got to stop for a minute.” There was this crack in reality where I looked at him and there was a crack in his face. I looked out to the trees in his yard. The trees had this crack in them. And that crack in reality was the last straw for me. I’d never read about that anywhere and I’d never heard of it, either. Ever. I always read The Ring magazine, I still read it and never once have I heard a guy say, After he nailed me, I saw a big crack in reality.

When Charles Portis died in February 2020 at 86 years old, of complications from Alzheimer’s, even some of his fans were surprised to hear he’d still been alive. His last brush with mainstream attention had been in 2010, when two good things happened to him. First, the Oxford American magazine presented him with an award for Lifetime Achievement in Southern Literature. Second, the Coen brothers’ adaptation of his sophomore novel True Grit (1968) premiered Christmas week, grossed a quarter-billion dollars worldwide, and was nominated for ten Oscars. The first adaptation from 1969—starring John Wayne, Glen Campbell and a young Kim Darby—is often misremembered as a classic by people who haven’t seen it lately. The Coens’ version—starring Jeff Bridges, Matt Damon and Hailee Steinfeld—is far more spirited and faithful, but let’s get back to the Oxford American party.

It was a black-tie fundraising gala held at the finest hotel in Little Rock, Arkansas, where Portis lived. (The magazine, founded in Oxford, Mississippi in the late Eighties, had relocated to Conway, Arkansas in 2004.) Mary Steenburgen was master of ceremonies, and the other marquee honoree was Morgan Freeman, whose purchase of the Ground Zero Blues Club in Clarksdale, Mississippi had kept it from going under and therefore constituted an Outstanding Contribution to Southern Culture. Portis hadn’t published a novel in nearly twenty years, but he turned up finely turned out, only to bolt for home before the ceremony began. By the time the organizers tracked him down he had changed out of his evening wear into khaki pants and a beige windbreaker. He was coaxed back to the gala but didn’t want to change again, so it was in this garb that he took the stage and accepted a golden statue of a rooster from then-editor Marc Smirnoff.

It’s a perfectly Portisean moment, in which an almost pathologically unassuming figure is coerced by circumstance into wagering a personal reserve of dignity against the overweening silliness of the world. The masterful touch—the one Portis would have invented if it hadn’t been invented for him—is of course the golden rooster statue, which was based on the magazine’s colophon but could not help alluding to True Grit’s Rooster Cogburn as well as Joann, “The College Educated Chicken,” from his debut novel, Norwood (1966). As far as I can tell, this was the last public appearance he ever made.

Portis was born in El Dorado, Arkansas in 1933. He joined the Marine Corps in 1952, saw combat in Korea, then studied journalism at the University of Arkansas. He held jobs at a string of regional papers before moving to New York in 1960 to work at the Herald Tribune, which sent him back South in 1963 to cover the civil rights movement, then promoted him to London bureau chief, a job once held by Karl Marx. (Portis liked to joke that if the paper had paid better, history would have been spared a lot of heartache.) In 1964 he quit journalism and moved back to Arkansas, which would be home base for the rest of his life, though he spent a lot of time traveling in Central and South America. He wrote Norwood in a rented fishing shack and sold it almost as soon as he finished. It was published to warm reception in 1966 and he never worked a straight job again.

The hallmark of Portis’s work is farce delivered with a straight face in successions of tightly choreographed set pieces, splitting the difference between the picaresque and the grotesque. He draws on a tradition established by Melville in Moby-Dick, and sustained across the generations by writers as varied as Mark Twain, William Faulkner, John Kennedy Toole, Ralph Ellison, Flannery O’Connor, Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon, Denis Johnson, Donald Antrim, Mary Robison, Paul Beatty, Percival Everett and Nell Zink.

“Anything I set out to do degenerates pretty quickly into farce,” Portis told Newsweek in 1985. “I can’t seem to control that.” But one should not mistake lightness for slightness. Portis is a comedian of the highest order, but he is finally—as all comedians must be—a moral philosopher, because comedy, like prophecy, is always grounded in a critique of the world as it is based on a vision of the world as it ought to be. I’m reminded of a remark of Flannery O’Connor’s, made in a brief preface to the second edition of Wise Blood, published in 1962, two years before the end of her life and four years before Portis’s debut. “All comic novels that are any good must be about matters of life and death,” O’Connor wrote. A few lines down, she poses a question: “Does one’s integrity ever lie in what he is not able to do?” For O’Connor’s Hazel Motes, the answer is yes: his inability to refuse Christ is the bedrock of his integrity and the path to his salvation, brutal as it is when it arrives. For Portis’s schemers, dreamers, dropouts, road-trippers, scammers and pilgrims, the answer varies based on who is driving the given story and what it is they’re after. But Portis, unlike O’Connor, has a baseline level of respect for anyone stubborn enough to sustain whatever quest they may happen to be on, separate from the question of whether said quest is worth completing or if it ought to have been undertaken in the first place.

Such pioneer spirit is a distinctly American quality, and nobody embodied it more fully while also mocking it more ruthlessly than Portis in his five peerless novels. A new Library of America Collected Works gathers them together in one volume, supplemented by a judicious selection of “Stories & Other Writings”—all told 1,100 pages of handsomely bound bible-paper well worth your $45 and the mild eye strain. What comes into focus as you make your way through is a worldview that favors that old Emersonian notion of self-reliance, as well as the observation made by the man in Robert Frost’s “Mending Wall” that “good fences make good neighbors.” These are loquacious, peripatetic novels written by a guy who thought that people ought to stay home and keep to themselves. Exactly none of his characters are able to do this, and it is from their extravagant failures of silence and stillness that Portis’s comedy derives.

“Anything I set out to do degenerates pretty quickly into farce”

Charles Portis

Norwood, the novel borne out of the fishing shack, is appropriately country-fried in its concerns. It begins, “Norwood had to get a hardship discharge when Mr. Pratt died because there wasn’t anyone else at home to look after Vernell. Vernell was Norwood’s sister. She was a heavy, sleepy girl with bad posture. She was old enough to look after herself and quite large enough, but in many ways she was a great big baby.” Norwood takes his discharge, “which he felt to be shameful,” and heads home on a bus from the East Coast to Ralph, Texas. Then he remembers that a fellow Marine named Joe William Reese owes him seventy dollars. This uncollected debt haunts him all the way back to Ralph, and eventually leads him to take a job with Grady Fring the Kredit King, a local entrepreneur who needs a car delivered to New York City, where it’s rumored that Reese has been living.

From the Paris Review

Interviewed by Larissa MacFarquhar

COURTESY OF FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX

COURTESY OF FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX

Robert Gottlieb is a man of eclectic tastes, and it is difficult to make generalizations about the authors he has worked with or the hundreds of books he has edited. In his years at Simon & Schuster, where he became editor in chief, and as publisher and editor in chief of Knopf, he edited a number of big best-sellers, such as Jessica Mitford’s The American Way of Death, Robert Crichton’s The Secret of Santa Vittoria, Charles Portis’s True Grit, Thomas Tryon’s The Other, and Nora Ephron’s Heartburn. He worked on several personal histories, such as Brooke Hayward’s Haywire, Barbara Goldsmith’s Little Gloria . . . Happy at Last, Jean Stein and George Plimpton’s Edie: An American Biography, and the autobiographies of Diana Vreeland, Gloria Vanderbilt, and Irene Selznick. He has edited historians and biographers including Barbara Tuchman, Antonia Fraser, Robert K. Massie, and Antony Lukas; dance books by Margot Fonteyn, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Natalia Makarova, Paul Taylor, and Lincoln Kirstein; fiction writers such as John Cheever, Salman Rushdie, John Gardner, Len Deighton, Sybille Bedford, Sylvia Ashton-Warner, Ray Bradbury, Elia Kazan, Margaret Drabble, Richard Adams, V. S. Naipaul, and Edna O’Brien; Hollywood figures Lauren Bacall, Liv Ullmann, Sidney Poitier, and Myrna Loy; musicians John Lennon, Paul Simon, and Bob Dylan; and thinkers such as Bruno Bettelheim, B. F. Skinner, Janet Malcolm, and Carl Schorske. He has helped to shape some of the most influential books of the last fifty years, but nonetheless finds it difficult to understand why anyone would be interested in the nitpicky complaints, the fights over punctuation, the informal therapy, and the reading and re-reading of manuscripts that make up his professional life.

Gottlieb was born in New York City in 1931 and grew up in Manhattan. He read “Henry James, Jane Austen, George Eliot, Proust—the great moralists of the novel. Of course,” he says, “I admired the Russians tremendously, but I didn’t feel that I’d learned anything from them personally. I learned how to behave from Emma—not from The Brothers Karamazov.” He graduated from Columbia in 1952, the year his first son was born. (He has since had two more children with his second wife, actress Maria Tucci.) He spent two years studying at Cambridge and then in 1955 got a job at Simon & Schuster as editorial assistant to Jack Goodman, the editor in chief.

Publishing was a very different business in the fifties. Many of the big houses were still owned by their founders—Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer owned Random House; Alfred Knopf owned Knopf; Dick Simon and Max Schuster were still at Simon & Schuster. As a result, publishers were frequently willing and able to lose money publishing books they liked, and tended to foster a sense that theirs were houses with missions more lofty than profit. “It is not a happy business now,” says Gottlieb, “and it once was. It was smaller. The stakes were lower. It was a less sophisticated world.”

In 1957, Jack Goodman unexpectedly died, and at about the same time, Simon & Schuster was sold back by the Marshall Field estate to two of its original owners, Max Schuster and Leon Shimkin. Schuster and Shimkin didn’t get along, things became strained, and within a few months most of the senior staff had left the company. The owners neglected to hire anybody new, and so suddenly, as Gottlieb puts it, “the kids were running the store.” Within a few years Gottlieb became managing editor, and a few years after that, editor in chief. Then, in 1968, he left Simon & Schuster to become editor in chief and publisher of Knopf.

Next to reading, Gottlieb’s grand passion is ballet, and from the mid-seventies to the mid-eighties, while at Knopf, Gottlieb served on the New York City Ballet’s board of directors, in which capacity he organized ballets from the company’s repertoire into programs for each season and oversaw its advertising and subscription campaigns. (A third, lesser, passion of Gottlieb’s is acquiring odd objects—including vintage plastic handbags, of which he has a notorious collection.)

In 1987, at the invitation of its new owner, S. I. Newhouse (who also owns Knopf), Gottlieb left Knopf to take over The New Yorker. The announcement of his appointment was received with undisguised hostility by the magazine’s staff, who suspected Newhouse had ousted Gottlieb’s predecessor, the venerated William Shawn, editor since 1952, against his will. Dozens of the magazine’s staff members signed a petition requesting that Gottlieb refuse Newhouse’s offer. He didn’t. “I never took it personally,” Gottlieb explains. “I knew that the same thing would have happened to anyone. I didn’t even read the names of the people who signed the letter, many of whom were good friends of mine. I knew that I felt a lot of goodwill toward the magazine, and I assumed that it would prevail. And, indeed, once I got there, everyone was wonderful, couldn’t have been nicer. I just got to work, and everybody got to work with me.”

In 1992, Gottlieb agreed to retire from The New Yorker to make way for former Vanity Fair editor Tina Brown. (He says he told Newhouse when he was hired that he would be a curator rather than a revolutionary, and that if Newhouse wanted radical change he should find someone else.) Then sixty-one, Gottlieb decided he didn’t want to begin running something else, and offered his services to Sonny Mehta, who had taken over Knopf when Gottlieb left. Since then, Gottlieb has been working gratis for Knopf (he received a large settlement from Newhouse when he left The New Yorker) on books like John le Carré’s The Night Manager, Katharine Graham’s autobiography, Mordecai Richler’s forthcoming book on Israel, Arlene Croce’s study of Balanchine, David Thomson’s biographical dictionary of the cinema, Eve Arnold’s retrospective and various New Yorker cartoon books.

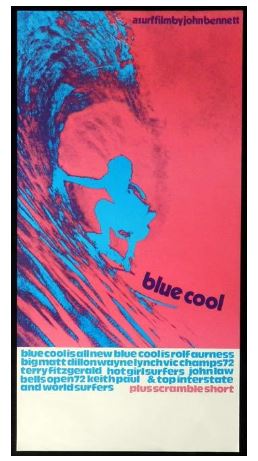

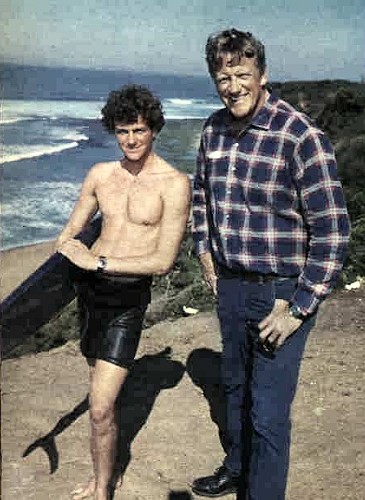

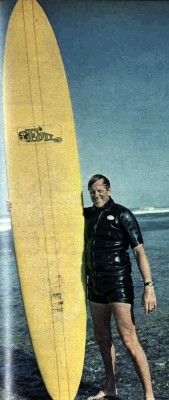

The Farmer’s Daughter was meant to be his big break, but instead, James Arness opted for surfing breaks. The Minnesota native nabbed a role in the 1947 Loretta Young flick because it was about a Swedish-American woman. Arness had a knack for Scandinavian accents, so he ended up playing one of her brothers.

The towering Arness was new to Los Angeles, having headed west after recuperating from a war injury. A German machine gun had shattered the bones in his leg during the Battle of Anzio in Italy, back in ’44. The wound had left him with a shorter limb, slight limp, and lifelong pain. But his fascinating World War II experience is a story for another time.

After The Farmer’s Daughter hit theaters, Arness found casting calls far more crowded. Eager men were flooding Hollywood after the war. Competition was fierce. Arness retreated home to the Land of Lakes to visit his mom, who had recently married.

Arness drifted back to California, and took a job setting up bowling pins in an alley on Balboa Island, surfing in his off time. This was the summer of ’47. The lure of the waves became louder than his acting ambition. He forgot about booking roles. Instead, the 6′ 7″ guy headed south to San Onofre beach. He picked up odd jobs here and there, and collected unemployment checks that came to him following The Farmer’s Daughter. He slept in his car or on the beach. He followed the waves.

“Our mecca was San Onofre, and we named our fast-growing crowd the San Onofre Surf Club,” Arness wrote in his 2001 autobiography. “We just camped on the beach and spent a few days catching the big ones.”

San Onofre was on the land of Camp Pendleton, and U.S. Marines had beach houses along the shore. Arness and his surfing buddies began squatting in the unused Marine bungalows, dragging in furniture from a dump. Eventually, a Marine showed up and ordered the squatters to clear out in two hours. The Surf Club moved back outdoors but stayed on the beach, being sure to keep tidy. They shared bottles of Muscatel wine and idled.

“Just taking in the sun and surfboarding as we pleased was enough for us,” Arness recalled. “It was beautiful there, an unforgettable experience.”

One day, a car tore down the beach in haste, kicking up a cloud of sand. An old friend of Arness hopped out with a box of letters. He dumped a pile of fan mail on Arness, which had poured in following The Farmer’s Daughter.

“He chewed me out for wasting my time lying on the beach when I could be having a career in movies,” Arness said. “My beach bum friends had not known about my acting.”

This passionate pal, Ed Hampel, urged Arness to come with him to an audition. He landed a role in the play. The rest was history.

It wasn’t all for naught. Years later, in 1970, his son, Rolf Aurness (that’s the original spelling of the family name), became World Surfing Champion.

Pictures by Les Gorrie