Is it right to say that your ‘Under Wartime Conditions’ album was influenced by that particular period.’

Yes it was because (A) I was very poor, (B) there was a miners strike going on. That whole period in the ‘80s politicised me and I’m not a political sort of man, or wasn’t. So from the mid to late ‘80s I became quite political. ‘Summer in a Small Town’ was about that. I was watching not just an irresponsible government doing things but I was watching the very threads of the social tapestry of the country, that I had known, loved and grown up in being interfered with. And that interference, the legacy of that has filtered down through to what we have now.

We opened the podcast with ‘Illya Kuryakin Looked At Me’ that you released a few years later.

That was actually a poem before it was a song. That was quite unusual as I wasn’t writing poems then. It was a stream of consciousness. It was a shopping list of everything I liked in the ‘60s. It took me to the early ‘80s to realise that the ‘60s had been quite good. It was when Mrs Thatcher started stomping on steelworks and miners. Erasing communities and starting wars. I began revisiting my past and eventually the song came out of the poem.

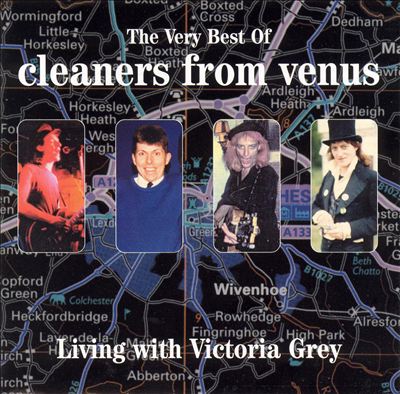

Looking back at The Cleaners From Venus, especially the compilations, it’s just track after track of hit singles that never were. ‘Julie Profumo’, ‘A Mercury Girl’, ‘Girl On A Swing’, ‘Mad March Hare’.

I sort of liked them at the time you know. I wrote them and thought ‘These things are quite good. Surely the world won’t be content to see me starve when I’m producing stuff of this quality.’ But they were only too happy to see me starve by never giving me any money. I thought it was a grand comedy. In my lighter moments I knew they were good. I had darker moments I thought ‘I’m not selling them because they are rubbish.’

But I wasn’t selling them because the whole music business is dominated by a place called London.

London is a place where people talk like this [adopts public school business voice] ‘Good man. I’ve got a window for you Wednesday’ and takes too much of the devils’ dandruff and all that bollocks. So I didn’t like London and I didn’t like business and I decided ‘What if I conduct an entire music career without any fame or any money?’. I came to the conclusion, even now 30 odd years later that it’s much more fun doing without the fame or the money as people who are twats don’t interfere with you. [laughs]

You get to do it your way.

Yeah. There was no one to tip their finger and say ‘Twangy guitars are on their way out Martin.’ Or say ‘I think you should be a little better. You were a bit flat there.’ Imperfection is an ideal striven towards.

I made an album with Andy Partridge and he’s quite a perfectionist. So I went along to see what would happen if I went for perfect. And it was very good and it was alright. But in the end I go back to doing things kind of instantly because I like it. I don’t think anyone one would like me in the music industry for that reason and I certainly wouldn’t like to go to the party. I’d find that repellent. Especially when you see old punks and people like that. You see people turning up in their bow ties turning up at award ceremonies. I think ‘Hang on. Weren’t you a rocker. Surely you wouldn’t go to these things and rub shoulders with these people.’ But they do, don’t they.

So you’re not a perfectionist.

No, it’s the mistakes that make it. It should be my motto ‘Mistakes make the man’!

After this period you went on to become known as one of Britain’s most successful living poets.

I’ve been told I’m England’s most published poet because I’ve had a poem in a national newspaper every week for near a quarter of a century. When I was writing for The Independent it was sometimes three a week and I’ve just got this massive body of work. It doesn’t necessarily mean it’s all good. Some of it is though and I don’t treat poetry as a special thing that only some people in universities have. Academia and Oxbridge in particular have hijacked poetry and treat it as only they understand it. They make it so obscure that nobody reads this stuff anymore because it’s so difficult to understand. It shouldn’t be. The way they combat that is to create these prizes like The Oxford Chair of Poetry. I mean, what the frig is that!

I don’t believe them and I don’t believe in the Arts Council. I don’t trust them, I’d like it all torn down. [laughs] In a kindly way! The best accolade for me is that it’s helped pay my way for 25 years. You just have to write what people want and most poets do not.

That’s what you’ve got in common with John Cooper Clarke.

John’s a friend of mine and is a great poet. He wanted to be a comedian and became a poet because he wasn’t getting work as a comedian, I think. I wanted to be a musician and became a poet at a point I couldn’t be a musician. I could probably do John as I know his material so well.

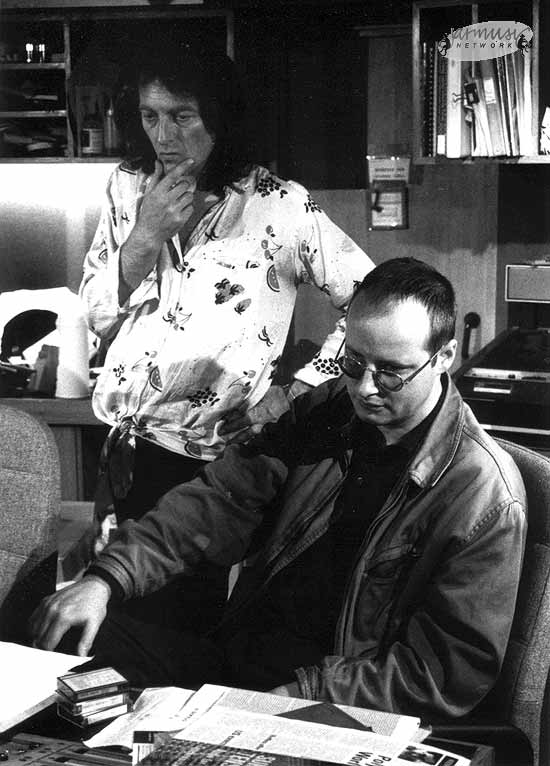

John Cooper Clarke (left) and Martin Newell (right) (photo from http://blog.fixemag.org/post/28420514019/myu-zik)

He’s done a poem for you that’s very complementary.

He wrote it a long time ago when he first met me. [adopts convincing John Cooper Clarke voice] ‘The man has got two jobs to do. He’ll satisfy your horticulture needs. Then he’s got a gig in Leeds. Who’s that? Martin Newell.’ [laughs] It’s like an Alan Whicker convention when we get together. Most of the time we are telling each other jokes and he’s always got more than me. He went head to head with my younger brother once and he lasted an hour and 15.

However in the early ‘90s things started hotting up on the music front again with probably your best known album ‘The Greatest Living Englishmen’. Which Andy Partridge of XTC produced who I’ve always loved. You touched on this briefly earlier, what was it like working with Andy?

Andy had just finished working with the young Blur at the time on what might have been ‘Modern Life Is Rubbish’. I think Stephen Street ended up producing them. Somebody wanted to put me and Andy together because they thought we’d work together. I think they thought I was a bigger XTC fan than I was. I liked them but didn’t know that much about them. Lol and Giles from The Cleaners from Venus were huge XTC fans but I tended to like their singles.

So I met Andy in November ‘92 and he liked my poetry. He’d bought one or two of my poetry books but didn’t know I did music. After he became aware I could write songs he said ‘How come I haven’t heard of you?’. So I had to explain how I hated the music industry and so on. But we ended up working together and we got on like a house on fire. We were like twins who had been separated at birth. Same sense of humour. I think he has a rather different attitude in the studio. He’s not a slap it down and leave it merchant like I am. So I said ‘One of us is going to be the producer and since it’s you I’ll do exactly what you say.’ And that’s exactly what we did. Andy has said he’s somewhere between Santa Claus and Mussolini in the studio.

But someone’s got to be the governor and it just meant I was free to just go and be the artist. I picked a couple of vetoes and just said once ‘You do realise you’re making a Martin Newell album and not an XTC album ok.’ He was very gracious about it. He said ‘Of course.’ A lovely bloke. I didn’t fall out with him but there came a time when we moved on. We were quite close at one point. Very good chap.

Martin Newell (left) and Andy Partridge (right), during the recording of “The Greatest Living Englishman” in 1993 from http://jarmusic.apwb.com/gallery.php?getgallery=main