Ween – Tried and True

Silver Jews – Dallas

The Flatlanders- Dallas

Beyond Sunset

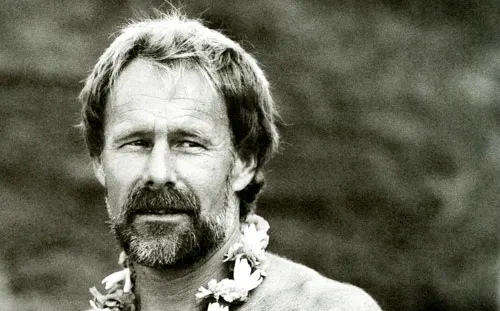

Derek Hynd profiles Roger Erickson, the gladiator of Waimea.

Tom Carroll returned home two seasons ago from Hawaii with a ginger-colored beard. “Just like Roger Erickson’s,” as Tom put it. It smacked of hero worship. The beard came off after a week of sloppy surf, but the intrigue remained.

Last winter, walking into the Sunset Store on Oahu, I saw that Roger Erickson had signed a one-man protest next to his name on the list of Eddie Aikau Invitational invitees, pledging $15,000 to charity if he won. I’d already heard stories, opinions and predictions about him—some good, some strange. No one really knows how he operated so powerfully on his own.

Then, a big moment.

Roger was running on the soft sand between Rocky Point and Pipeline, when he angled up to the Pupukea deck that held Flippy Hoffman, Fred Van Dyke and myself. Thundery things filled me, in the face of a man who looked so nice, yet so deadly. He was 41, with a gladiator’s build, but his eyes had it all: life, death, and wisdom. Here was power, in mind and body. A defined human being. We met. Suddenly, I wanted a beard.

Playa del Rey, Los Angeles. Summer of ’65. “It was the best year of my life. Everything was coming together: a year out of high school, double-dating at the drive-in, racing at Lyon’s Drag Strip, surfing and hanging out on the beach—all that stuff. In ’66, it all fell apart.” Roger pauses. “I joined the Marines to avoid being conscripted. I didn’t want bad training if I was going to Vietnam.”

Fresh out of boot camp, Roger married his high school love, and honeymooned in Hawaii. “Just me and my girl, living at Rocky Point. I surfed big Sunset and Waimea, and she was there when I got out.” Two weeks after that, Roger sailed out of San Diego in early morning darkness. “I remember looking over the railing of the boat, smoking my bowl of pot, thinking, ‘Man, what am I doing?’ I’d just left my whole life behind. I actually thought about jumping off.”

On February 6, 1967, he entered another world. Da Nang fist, then southwest to Hill 55. On the way, a sniper nearly picked Roger off. It got him excited. He volunteered to go on point. Nobody did that.

On quiet nights, Roger thought about the beauty in everything he saw, and thought about his recent past. “I knew better, but at times it was all so serene out there. And with emotions running through you, you’re trying to relate to your life back home, and for me it was . . . ‘What’s she doing now? What is she doing now?’ That was my overriding emotion all through Vietnam.”

Roger’s squad was under fire and in retreat, up by Hill 55. “A bullet came so close to my head that I felt it pass, and at that point I got so focused returning fire that I lost track of time. When I finally turned around, everyone was gone. It was just me. I saw movement, and retreated through the field, started running, and a mortar landed between my legs. It didn’t go off.”

Another time, Roger saved the life of a friend who’d tripped a mine. Roger was injured as well, but not as badly. He dove on his burning friend, smothered the fire, then collapsed. Earned himself a Bronze Star.

The war just kept coming. Out of the infirmary, Roger was airlifted straight to Khe Sanh. It was quiet when he arrived, but was soon to become one of the heaviest battlefields in military history, with Roger in the middle. Everything was chance, from taking a shit, to sleeping, to going on point. It rained two days out of five. Jungle rot was everywhere, and plagues of mosquitoes descended and devoured. He was truly in hell now, and interest began to fade. His own description: “I was a walking zombie.”

Late in ’67, Roger got his R&R pass, along with malaria. By the time he arrived back at Da Nang for the trip to Hawaii, he was nothing but shakes, sweats, and chills. “Somehow I hid my condition, because I didn’t want to get put in the hospital again. As soon as we got to Honolulu, I jumped the first plane home.”

Back in Playa del Rey, everything had changed. Incredibly, just 10 months had passed since he’d left. Roger was 21. He spent five days in town, three of them in bed. People avoided him. The word went something like, “Roger’s back from Vietnam, and he’s twisted.” He smelled like the bush, and looked out of his mind. His wife had split, hippied out in paisley and granny glasses. “It didn’t matter by that point. The way I figured it, I was going back in at Khe Sanh, and wouldn’t be coming out. You can’t imagine how sick I was at that point—in every way.”

After returning to Da Nang, Roger spent a month in the hospital, and then sure enough was ordered to Khe Sanh—where the hell he’d experienced before soon expanded tenfold. After walking in the jungle for two days on patrol, Roger was on his way back to camp when the North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive. The world had never seen a battle like it. Hill 881 was no more, and Khe Sanh became the most crater-ridden location in history. Survival itself was a ridiculous longshot. Survival followed by a return to normalcy was a complete impossibility.

Playa del Rey. Summer of ’68. “I was the decorated Vietnam Marine, back in town, and I was meant to set a good example. I surfed, but basically I was racing bikes. My forte was going as fast as I could. I remember flying down Imperial, near LAX. The police were on me, and that got me all jazzed. I had a couple of outstanding tickets, and no license, so I went for it. Here come the sirens, and all I could think of was, ‘Wow, unreal! If I get through the tunnel up there, I can escape.’ But they ran me down on the curve past the tunnel. I took the corner so fast—had my back wheel on the edge of the gutter, riding out the curve. They threw me in jail for two weeks.”

By 1969, Roger had a dark reputation around town. The full impact of Vietnam had still not been felt in America, and any veteran who opened his mouth against what was happening was a Commie-lover. Few civilians saw the vets’ point of view, or knew of their problems.

Roger went deeper into his Easy Rider mode. At a Venice Beach concert that year, he saw an old biker getting billy-clubbed by several policeman. “I saw a friend in trouble, and starting running over. Hands down, totally passive, just wanted to try and settle things down. One of the cops saw me coming, and next thing the club was coming down on my head, then I’m fighting five or six of them.” Roger went to court, refused to plea-bargain, argued self-defense, and got a 10-month prison term for his troubles. Out in late 1970, he got into it with five bikers at a party in the middle of L.A.. One of them had a baseball bat. A busted arm and a fractured skull for Roger, and thereafter his involvement with bikers was terminated.

I learned all of this during a chess game with Roger, not long after we met. He wasn’t proud of his past. As Roger saw it, he’d had a destiny until Vietnam ripped it away. Not until the mid-’70s was he able to think about the future, and a challenge relative to Vietnam—a fresh test of mind and body, but this time by his own choice, on his own terms.

Roger knows the limits of human endurance in more ways than any other surfer. As he laid my king over on the chessboard, he slowly said that the flashpoint of his memory was no longer Khe Sanh. Now it was that afternoon in 1976, when he was a link in the human chain that saved big-wave surfer Kimo Hollinger from drowning during a huge swell at Waimea. As outstretched hands met, the point of contact burned into Roger’s soul: the difference between life and death.

Roger Erickson had a new destiny. He bought Kimo’s board.