Tag: Culver City Kook

The Blasters – Common Man

John Prine – Paradise

Everly Brothers – Crying In The Rain

Peter Lorre Documentary

The Blasters – I’m Shakin’

Warren Zevon – Boom Boom Mancini

In the midst of a phantasmagoria of worn-out mangled faces, scarred cheeks and necks, twisted, pocked, crushed and bloated noses, missing teeth, brown snags, empty gums, stubble beards, pitcher lips, floppy ears, scores, scabs, dribbled tobacco juice, stooped shoulders, split brows, weary, desperate, stupefied eyes, under the lights of Center Street, Tully saw a familiar young man with a broken nose.

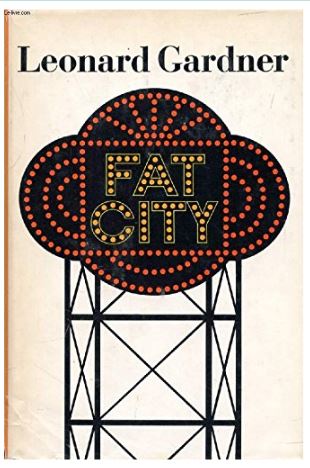

Leonard Gardner

Fat City, Fifty Years Later: An Interview with Leonard Gardner

By David Lida

From: The Paris Review

Fifty years ago, in 1969, a boxing novel unlike any other that has seen the light of day, before or since, was published. Fat City, by Leonard Gardner, upends the triumphalist clichés of boxing stories, in which a palooka from nowhere overcomes all obstacles through fierce dedication and hard work and wins the title.

To say that Fat City is about boxing would be like saying that In Search of Lost Time is about parties in Paris or Moby-Dick is about whaling. Boxing is the setting, and it’s one that Gardner knows firsthand. But the novel is about hope, illusion, and love, and the corruption and self-deception that destroy those things. It’s a lean and sinewy novel, without a single surplus sentence. Considered a masterpiece—by Joan Didion, Denis Johnson, and Raymond Carver, among others—the book is still in print at New York Review Books.

Fat City follows two would-be boxers—one, eighteen-year-old Ernie Munger, is on his way up, while the other, twenty-nine-year-old Billy Tully, is in a downward slide. No matter how hard they train, no matter how much they believe in themselves, no matter who they have in their corners, neither will ever get anywhere near a championship belt.

The book is set in the city of Stockton, in California’s Central Valley, where Gardner grew up. Stockton is noted for its high crime rate and its low literacy level. It is the second-largest U.S. city to have ever filed for bankruptcy. Ernie and Billy frequent greasy, fleabag hotels; sweaty gymnasiums with flooded, blocked drains; blistering fields where boxers earn a day’s pay picking onions or tomatoes; and violent skid row bars where patrons nurse their cut-rate shots and beers. In 1972, Gardner wrote the screenplay to adapt Fat City into one of the saddest movies ever filmed, directed by John Huston.

Gardner lives in Marin County, California, about a hundred miles from Stockton. He is now eighty-five, tall, lanky, and cordial, with a full head of hair more brown than gray. He is under contract for a second novel. I caught up with him in Berkeley to talk about the book, its film adaptation, and his life as a writer.

INTERVIEWER

Fat City exposes a reality about the lives of most boxers. I wonder whether you had that in mind when you wrote the book—knowing that you had a truth to tell that was unlike anything that had been published before.

GARDNER

I got into amateur boxing as a teenager in Stockton, and had some amateur bouts, but I never boxed professionally. Still, I felt like I had a story. The opening of the book is based on experience. There was a boxer, he’s dead now, his name was Johnny Miller and he was a ten-round main-event fighter. I’d seen him fight in Stockton, then he just went a little overboard and became kind of a drunk and had to drop out of boxing for a while. One day, I was in a gym punching on a bag—I had a bag in my garage, and I learned how to punch that bag like a wizard. He came in there and asked me whether I would spar with him. And I felt, Jesus, I’ve been acting like I’m a boxer, but I had been boxing only with kids in the backyard. I’d seen him box, but I couldn’t say, No, you’re a professional. He was in really bad shape, but I was still spooked. I was thinking this guy will kill me.

I had dreamed about being a boxer. Out in the garage I punched about ten rounds on the bag every day. You use your imagination and you’re like, I’m knocking the shit out of Sugar Ray Robinson! So I felt, This guy is calling my bluff and I have to box with him. Maybe he had a horrible hangover or something—I don’t know. I was a tall, long-legged kid, and I had footwork. I ran rings around this guy, popping in little jabs. I actually did a good job of surviving. I could pop him with my jab and he’d swing and he’d miss and I’d be out of the way. And so naturally he had to save some self-esteem by thinking, I’ve discovered a great talent here! He said, “You gotta box, kid.”

INTERVIEWER

Books and movies about boxing tend to be about contenders or champion fighters. Even the seedier stories are sort of glamorized. But Fat City is about people who will never in their wildest dreams be contenders.

GARDNER

When I was a kid, Stockton had a population of eighty thousand. It was a hot boxing town, and we never turned out a champion. There was nobody remotely like a champion.

INTERVIEWER

In the book, in the climactic fight, Billy is punched so hard in the ring that he literally sees the world divided into a zigzag. I read somewhere that this was based on your own experience?

GARDNER

I wasn’t trying to be a professional boxer anymore, but I had a friend in Santa Barbara who lived near my ex-wife. A real tough guy, an ex-marine. He asked me to spar with him. And I thought, Well, I don’t have to demean myself. I just assumed we were friends. I’m a little guy compared to him. He has shoulders like this and a little waist. He would run fifteen miles just for the hell of it. He had a heavy bag hanging from the tree and he worked on that every day. He wasn’t actively boxing anymore, but he was one hell of an athlete. So we sparred and I can’t remember whether I went one round or two before he hit me with this shot. I’ve never had a reaction quite like that to a punch. And I told him, “I got to stop for a minute.” There was this crack in reality where I looked at him and there was a crack in his face. I looked out to the trees in his yard. The trees had this crack in them. And that crack in reality was the last straw for me. I’d never read about that anywhere and I’d never heard of it, either. Ever. I always read The Ring magazine, I still read it and never once have I heard a guy say, After he nailed me, I saw a big crack in reality.